On a recent forum, someone asked, “What are the creativity killers in the art classroom?” Good question. What stops students from reaching their creative potential? There are some creative killers that seemed to come up frequently. The larger question though is, how do we combat these creativity killers? So, here are the three most common ones and some ways I combat them.

1. We kill creativity if we continue to allow students to believe they are not creative by nature.

Picasso said, “All children are artists. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” In art (and other subjects) some students are praised for their abilities and others are left to assume they just didn’t get that talent when talents were being handed out but that’s a fallacy.

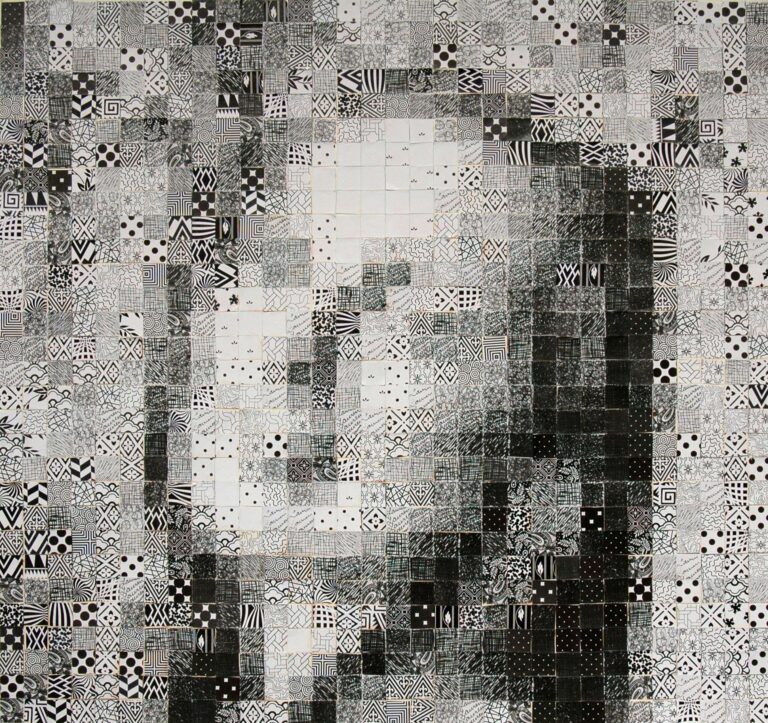

I also encourage people to separate creativity and art. Art and creativity are not identical twins but rather good friends that hang out together frequently. An artist can become very adept with art materials yet art is more than being technically adept, it is also about what you say. As developmentally predictable, middle and high school students are often impressed with highly realistic painting and drawing. Yet, it’s often been said that photography freed the artists from ties to realism. Photographers took over the task of making visual records and painters began to paint differently, exploring the brush stroke and giving birth to Impressionism and all that came after in art history.

Creativity isn’t owned by the art world though. Creativity is simply the ability to develop and express ourselves and our ideas in new ways. And creative thinking can be nurtured and is something all teachers should do. If you haven’t, immediately find Sir Ken Robinson’s Ted Talk Do schools kill creativity?

How to combat it: I simply present art as another subject where some students might have a natural aptitude but all can learn the skills and develop creative thinking. I remind them that my job would be pretty boring if everyone showed up to my class as fully formed artists. I remind students when they see a basketball player sink a basket we are all aware that the player must have practiced, developed his hand-eye coordination, built strength and stamina, learned basketball’s rules, and worked with teammates to coordinate plays. For some reason, there is a misconception about art that artists are just oozing with talent. I often quote artist Chuck Close who stated, “Inspiration is for amateurs — the rest of us just show up and get to work.” Art is work, although sometimes it’s fun work.

As teachers, we need to stop perpetuating that some students are artists or “superstars.” Malcolm Gladwell in his bestselling book Outliers: The Story of Success promotes that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to become highly skilled in a field. Even my students with “talent” or natural aptitude have to learn discipline and persistence. As a teacher, it’s so rewarding to see a child learn, grow, and create things they couldn’t have without instruction.

2. We kill creativity if we allow students to be afraid. Afraid of what? Taking risks, wanting to be perfect, and the need to achieve.

Kids need to play. They need to find joy in education. They need to fail and learn to persevere. They need to know they may not get it the first time. Or the second. And that is OK because there is more learning in failing than succeeding. More and more students hear the message that they must be the best. They must succeed. They must achieve. Yet, they lack those tools. I suspect there are few art teachers who haven’t been shown artwork and been asked, “Is it an A yet?” And how we cringe, right?

How to combat it: Allow students the ability to take risks and fail. I love teaching blind contour drawing. I love the moment they are so deeply involved in the act of seeing that you could hear a pin drop. Contrasted with the end of the exercise, the moment I allow them to look at the drawings they made and the bust of laughing and lots of chatter follows. No one looks at a contour drawing and feels successful. Yet, I hold them up and proclaim success while they laugh uproariously. Yet, they learned to see that day in a new way. They mastered risk-taking in that exercise, as uncomfortable as it might have been. Teach them to risk and to “fail fast” if I can borrow a term from programmers. As Fobes Magazine writes in “How To Fail Faster — And Why You Should.”

In the complex digital revolution era, trying to predict, control, and eliminate variances is a losing game. Reducing variance inevitably meets the law of diminishing marginal returns: the cost of reducing variance eventually exceeds the benefit. In addition, the goal of controlling and minimizing variance can be deceptive, because we don’t know what to measure in a complex environment that changes so rapidly, and we can’t control what we can’t measure. The minute we figure it out, what we need to measure has changed. For all these reasons, iteration instead of perfection is the more effective way to go.

I loved a story told by Sara Blakely, the woman who created Spanx and became a billionaire. She credits much of her success to the one question her dad asked her every night: “What did you fail at today?”

Some parents are content asking their children, “Did you have a good day?” or “What did you learn at school?” Not at the Blakely household. The question Sara and her brother had to answer night after night was this: “What did you fail at today?”

When there was no failure to report, Blakely’s father would express disappointment. “What he did was redefine failure for my brother and me,” Blakely told CNN’s Anderson Cooper. “And instead of failure being the outcome, failure became not trying. And it forced me at a young age to want to push myself so much further out of my comfort zone.”

In the art room, this looks like teaching students the art of being critiqued. Teach them to put their artwork up and to both receive and give criticism as well as compliments. As a teacher, don’t be afraid to say hard and necessary things, as well as be generous with compliments. In the art room, it looks like authentic feedback and grading that evaluates not just the product but the process. Honesty in addressing art room conduct and habits such as cleaning, caring for supplies, use of work time, etc are as important as discussing the elements of principles of design.

I always coach parents at the open houses to not wait until grades are issued but to ask their child about their art project, how they feel about their work, how the child and classmates conduct themselves, and how they feel about their progress and, eventually, their evaluations. I think this helps take the focus from the grades and allows for more authentic conversations about education. As a young teacher, I gave parents a shortlist of questions they could use to engage their children in conversation about the art room. Parents could jot down the answers and send them back with their children for extra credit.

3. We kill creativity if we allow students to not value or care about art.

I had a student come into my room before school asking if she could glue down a project she completed at home. “We just didn’t have glue!” she announced. That innocent comment stayed with me all day and beyond. “No glue?” I thought. “How do you raise children with no Elmer’s glue on hand?” I can’t imagine. Even my own niece came over and would go crazy with Play-Doh and paints because her mom didn’t like the “mess” at her house. We are limited in how much we can alter where our students come from and the value their homes place on art but we can widen their world and plant new seeds.

How to combat it: A student may say, “I’m never going to use art skills anyway.” My response? “Funny, I use my art skills daily but my math beyond middle school level and the language I spent three years learning, not much or not at all.” Our education is sneaky like that, it prepares us for possibilities and gives us a wide scope to build on and draw from. I teach them if they are interested in business, they may be involved in branding, which connects with the art skills I’m teaching them. I also recount how a friend from college became a web developer and called me to recommend books on color theory. It wasn’t enough to master HTML! He needed to understand color and how to pair it. Creativity is considered an important skill in the business world and “78% of college-educated workers over 25 wish they had more creative ability” according to a statistic from Adobe published in “10 Statistics You Need to Know About Creativity at Work.”

Are there more creativity killers? Of course, there are! But these are ones that seemed universal, mentioned by art teachers over and over again. All teachers will see these in action in their classrooms. Sometimes we will be seen as the creativity killer even. But, hopefully, more often than not, we are creativity’s fuel. We are the Jonny Appleseed of creativity, planting the seed for tomorrow’s artists and innovators.